It was Thanksgiving at the Heron’s Nest, and everyone was coming home.

James was back from Iraq and was miraculously not shot or blown up even a little bit, so he was eager to resume his role as quarterback of the Blacks, which was the name of one of the teams that played in the family’s annual Thanksgiving Day game. The other team was the Crimsons, of course, since crimson and black together meant Harvard and that’s where all the Jernigans went to college. The boys anyway.

It was a unclear to Mary how the teams were chosen in the first place. It seemed to go back several generations and involve various branches of the Jernigan family tree, each of which was assigned a number so they could be added and subtracted from one another in a weird calculus that could only be understood by those who bore that stately surname.

That was the explanation her husband, Roger Jernigan, gave her the fourth time she asked. “That’s something that can only be understood by Jernigans,” he bellowed in his stage voice. Then, poking their infant son in the belly, he cooed, “One day you’ll understand it, Harrison. Don’t you worry my boy. We’re all Crimson, all the way.”

Women and girls were not invited to participate in the big game. It was their privilege to serve as cheerleaders, hooting and shouting and calling out “Crimson!” or “Black!” as the situation required. Mary, who knew next to nothing about any sport, least of all football, hooted at all the wrong times and for all the wrong reasons. It was a wonder that Roger had even married her after the way she embarrassed him the first year he brought her to Thanksgiving at the Heron’s Nest.

This year, rather than embarrassing herself at the game, which was played on the wide front lawn of the estate between the main house and the lake, she took advantage of her place as the mother of the newest Jernigan and volunteered to act as nanny to the family’s younger children. There were nine of them altogether – five girls and four boys – all under the age of fourteen. Fourteen, she had learned, was the magical age when each young Jernigan was assigned a color, either through the presentation of a jersey or a set of matching crimson or black pom poms.

Last year, Joyce had received her pom poms and was very disappointed. She spent the whole weekend in her room crying about being assigned to the Blacks. It was taken in stride by the Jernigans who were visiting Heron’s Nest for the holiday. Roger’s sister Laura let it slip that every third or fourth child was disappointed in the math, but what could be done? It was just one of those things.

Mary frowned a little when she heard this, and she frowned again when she remembered it, ensconced as she was with the children in a fenced patio on the side of the house, where they could only just hear the hooting and shouting that accompanied the game. It was impossible at that distance to know who was winning or who was losing, and, to Mary’s great relief, any hooting and shouting that happened within the confines of the patio could not be misinterpreted or in any way considered wrong.

The toddlers waddled to and fro, enjoying the bright sun of that unseasonably warm Thanksgiving Day, while the older children crowded and sulked around the patio’s dining table, staring into their phones.

Jack was the sulkiest child of all. “I don’t understand why we have to stay all the way over here until we’re fourteen,” he whined. “I’m twelve next month, and I could run circles around all of them!”

“Maybe that’s the reason,” Mary smiled. Her joke was lost on Jack, who went back to his texting or YouTubing or whatever children did in those days.

Mary had just given Harrison a second bottle when the game ended. She knew it was over because she watched the men file into the house through the large windows that separated the patio from the kitchen. First the Blacks appeared, stomping and cheering and patting each other on the back. A little while later, the Crimsons wandered in, much more subdued and slower to laugh than their more jovial cousins.

“Oh dear,” Mary muttered, wrapping Harrison in an extra blanket and fretting about Roger’s mood. “Come along children, it’s time to go in and find your parents. Dinner’s coming soon.”

They all filed inside and the children disappeared into a throng of Jernigans. Mary brought up the rear, locking the patio door behind her. When she turned around, she was startled to see James standing just a few feet from her, tossing a football in one giant hand.

“Hello, James,” she said. “It’s nice to see you back safe and sound.”

“Mary,” he replied. “And what do we have here? This must be my new cousin Harrison.” James came close and pulled back the edge of Harrison’s blanket to look at his round face. “He’s lovely, Mary. I’m very happy for you.”

Mary forced a smile. “How was the game?”

“Oh we took it to them of course. The Blacks almost always come out on top. One might say you picked the wrong team when you married Roger.”

There were no knives in his words, but there might have been. Mary had met James first. Their eyes had met across a crowded ballroom at the annual Vanderbilt sorority ball. The way he looked at her that night made her feel as thought he’d loved her since years. She’d felt it in the soles of her feet.

Yet here she was, just a few years later, married not to this strong, beautiful man who professed his love so readily, but to his cousin. Roger was a good man, and he loved Mary in his way, but at that moment, standing so close to what could have been, she felt the full weight of her regret.

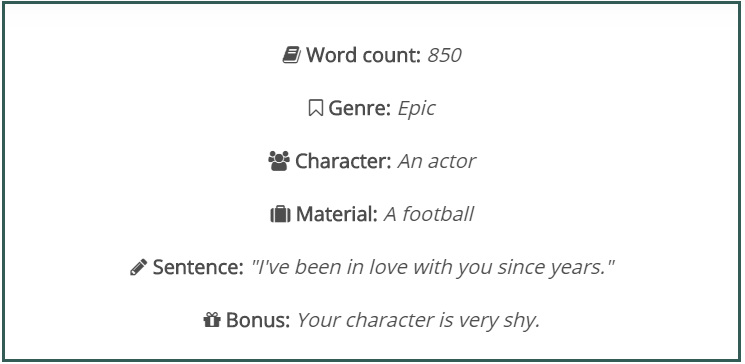

About Prompt-A-Day: The rules are simple. Every day, I generate a prompt using Story Shack’s awesome writing prompt generator. Then I set a timer for one hour. At the end of the hour, I post what I’ve got. Sometimes it’s decent. Sometimes it sucks. Sometimes I fail at the prompt. Sometimes I do okay. I do not edit, unless I find a typo, because I can’t help fixing those. Feel free to join in and post a link to your writing in the comments.

Comments (0)